Placemaking in Indigenious Sovereignty Efforts

Placemaking, as defined by Wikipedia, is the

“multi-faceted approach to the planning, design and

management of public spaces. Placemaking capitalizes on a

local community's assets, inspiration, and potential, with

the intention of creating public spaces that promote

people's health, happiness, and well-being.”

The approach of placemaking is a core principle in

contemporary Indigenous sovereignty efforts - the

reclaiming of ancestral lands and the traditional

resources therein through activism and policy centered on

independent management.

In her landmark book, Recovering the Sacred: The Power

of Naming and Claiming (1999), author Winona LaDuke

explores the plurality of Indigenous placemaking. From the

Klamath, Modoc, Yahooskin Paiute, Karuk, Yurok and Hupa

tribes of the Klamath river basin working to restore

stewardship of sickened rivers to the tribal communities

to the reclamation of horsemanship and homelands by the

Nez Perce tribes, placemaking is as diverse as the tribal

nations of this continent. In order to support these

efforts, each experience must be approached with a nuanced

understanding of place and community.

Place naming, a specific type of placemaking, is

another approach to sovereignty awareness and activism.

From land acknowledgement statements to traditional

greetings and name sharing, Indigenious language is a

powerful vehicle for identity reclamation. The ‘renaming’

of place, particularly sacred places, “inscribe the

landscape with meaning” (Gray & Rück, 2019) and challenge

accepted colonial narratives about the land and its

inhabitants.

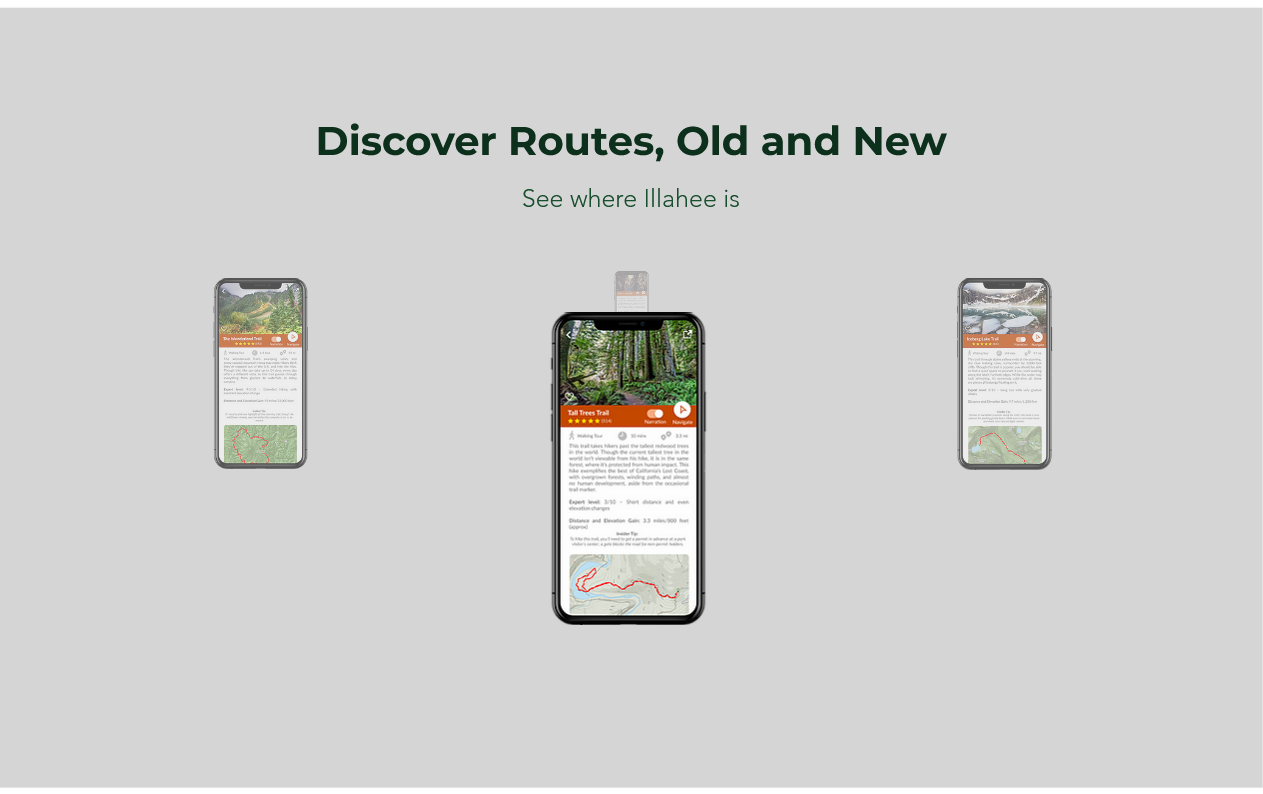

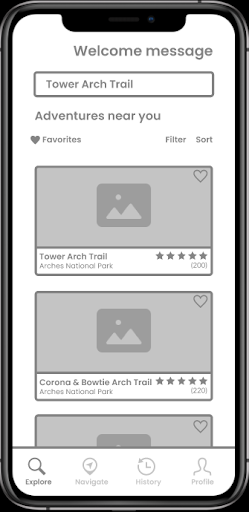

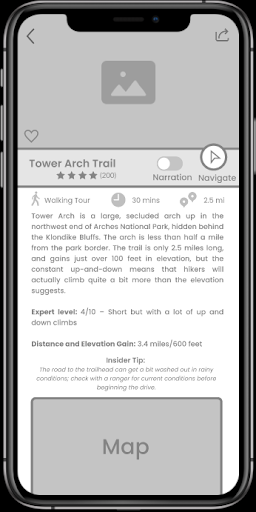

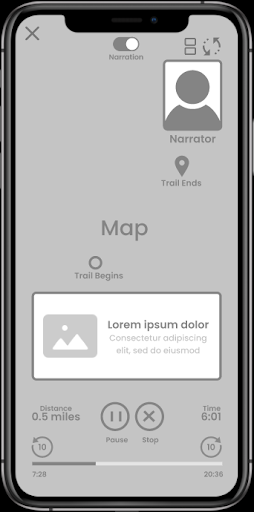

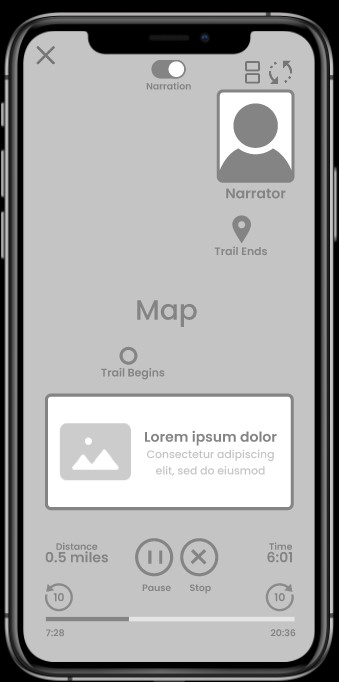

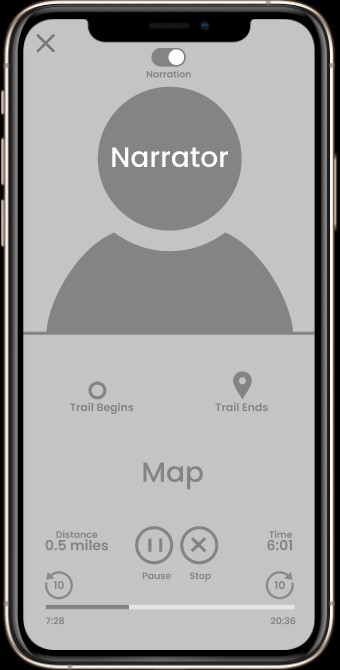

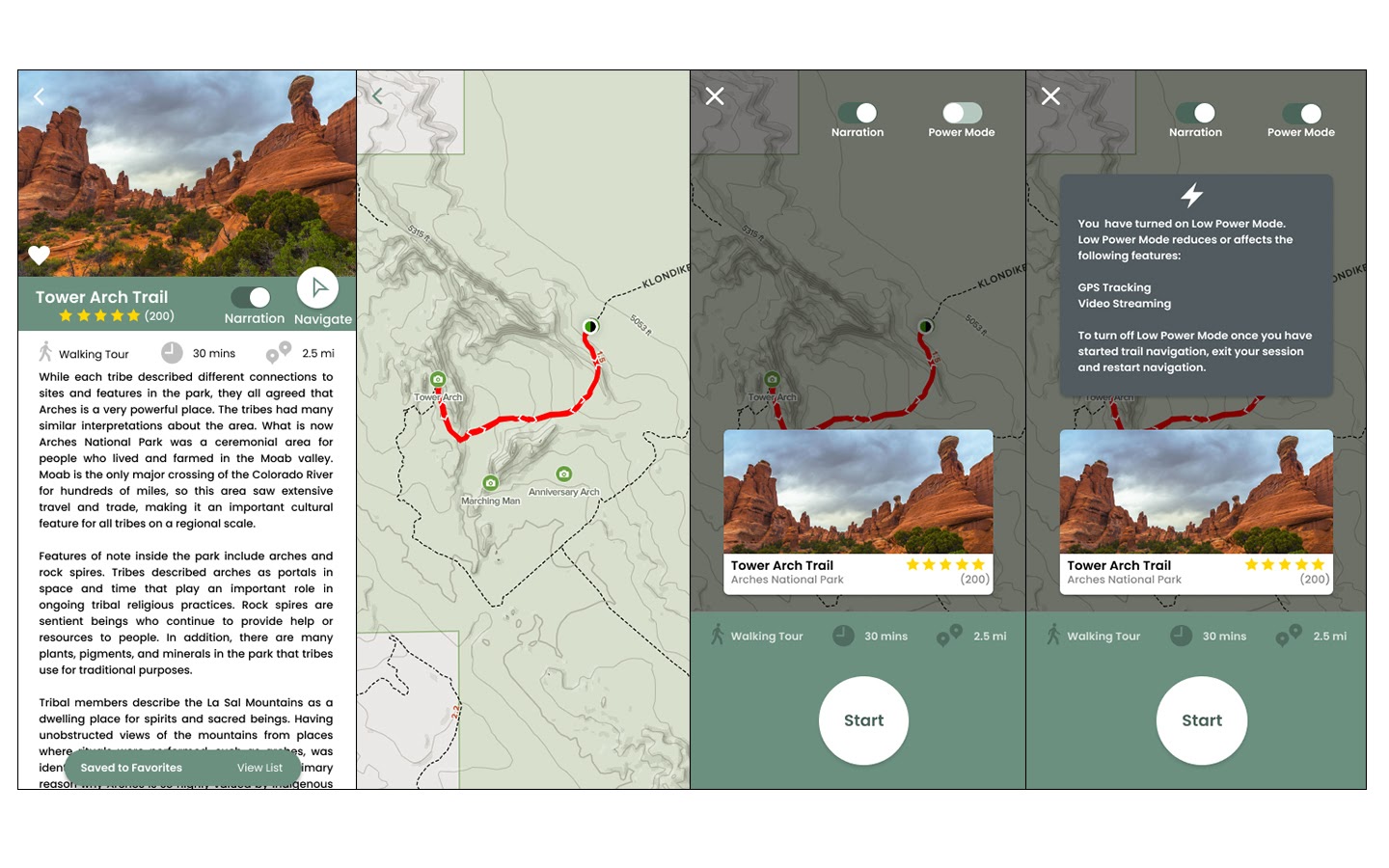

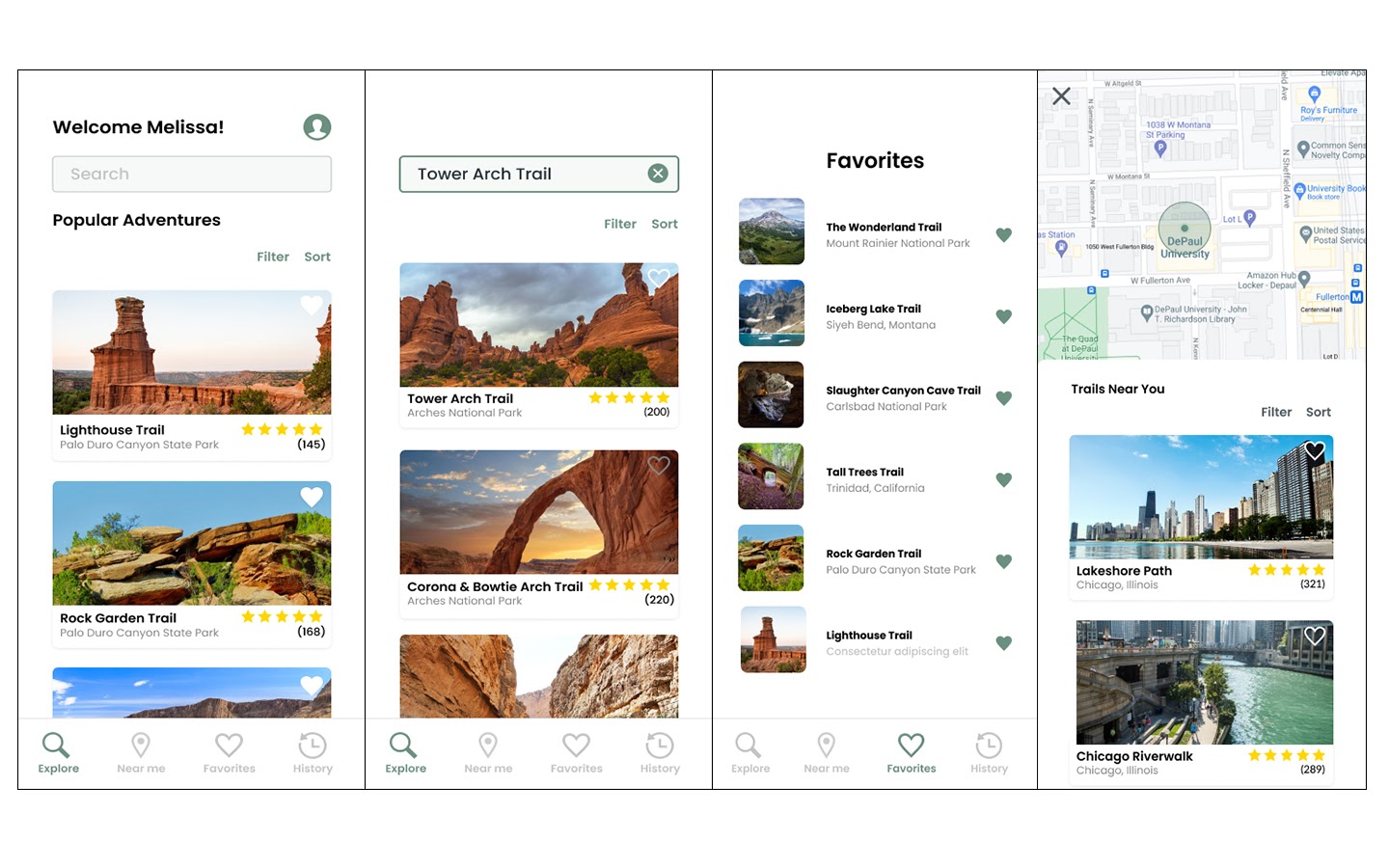

What if placemaking and place naming, as it relates to

Indigenious sovereignty efforts, could take the form of a

digital tool for all those experiencing a place,

Indigenious or otherwise? Could this tool support

cross-cultural education and awareness? Could this tool

support sovereignty efforts and ultimately influence

public policy?

HCI in Digital Placemaking

The role of HCI in digital placemaking has been

thoroughly researched and documented by HCI researcher

Clara Crivellaro and her colleagues in two key research

works: Contesting the City: Enacting the Political Through

Digitally Supported Urban Walks (2015) and Re-Making

Places: HCI, ‘Community Building’ and Change (2016).

In ‘Contesting the City: Enacting the Political Through

Digitally Supported Urban Walks’, Crivellaro, et al.

explore how “situated discovery” and “articulation of

issues at the intersection between the politics of place

making and city planning” can challenge normative

representations of place and give voice to marginalized

narratives. (Crivellaro et al., 2015, pg. 2966)

Crivellaro, et al. suggest that allowing for everyday

actions, uses and interactions to drive interrogations of

singular histories inherently contributes to a plurality

of experiences. This plurality is key in dismantling

ahistorical assumptions that uphold capitalist-colonialist

ideology and white supremacy and central to our design

research.

In Re-Making Places: HCI, ‘Community Building’ and

Change, a publication from the following year, Crivellaro,

et al. dig into how the intervention of “prevailing,

normative practices and existing spatial configurations in

order to support the articulation of values, issues and

open up the conditions of possibility,” with the paramount

importance of embodied storytelling explained:

“Stories find their value not in their

claims to legitimate truths about community and place.

Instead, it’s in their uncertain and open-ended nature,

and in how they emerge through varied, situated encounters

and contingent situations, that they posit an “equality of

intelligence” (rather than ‘sanctioned’ knowledge)]. That

they are plural, situated, partial and contingent doesn’t

discount them, rather it’s this that allows them to

contain the possibilities for the future.” (Crivellaro et

al., 2016, pg. 2966)

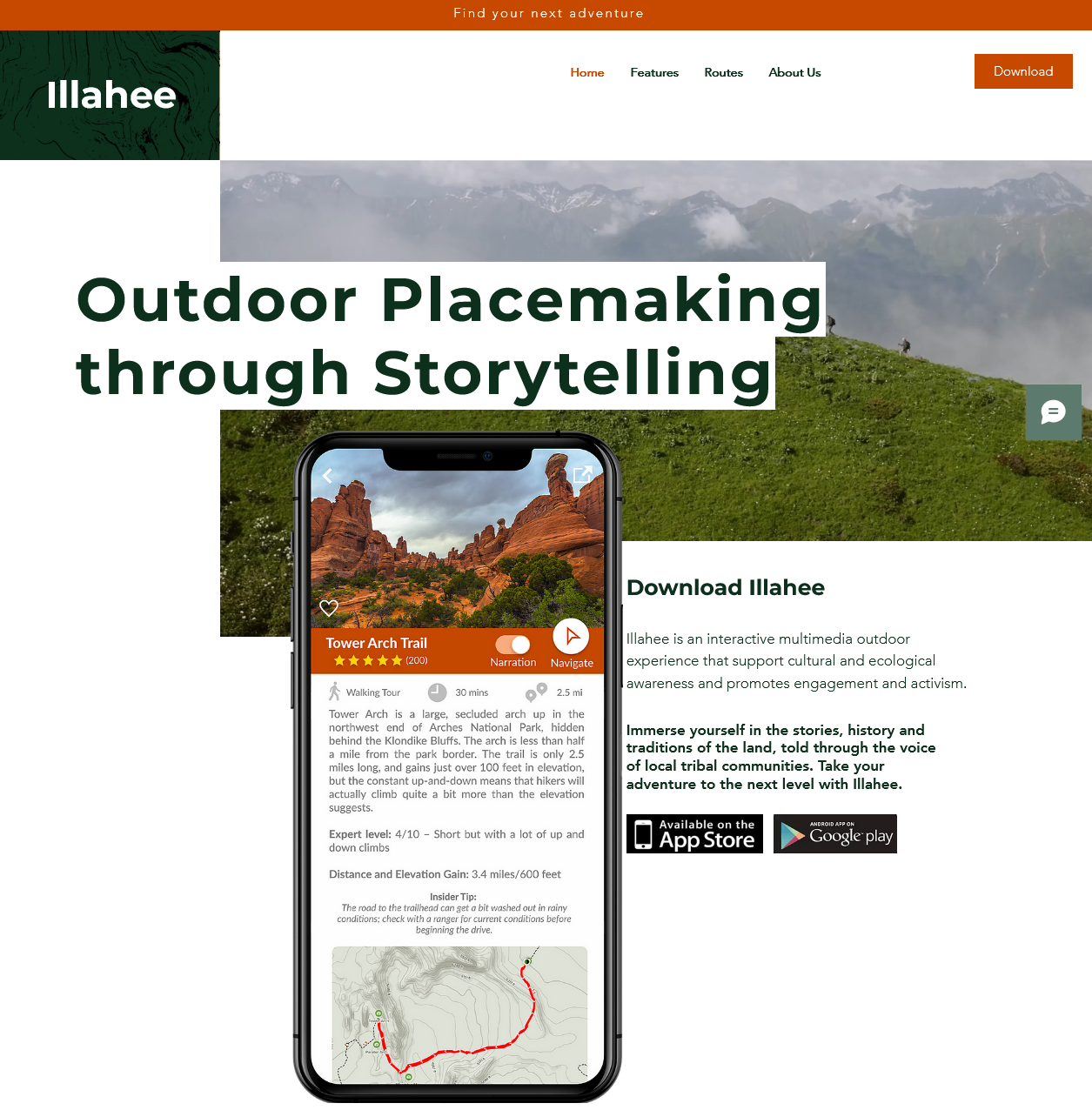

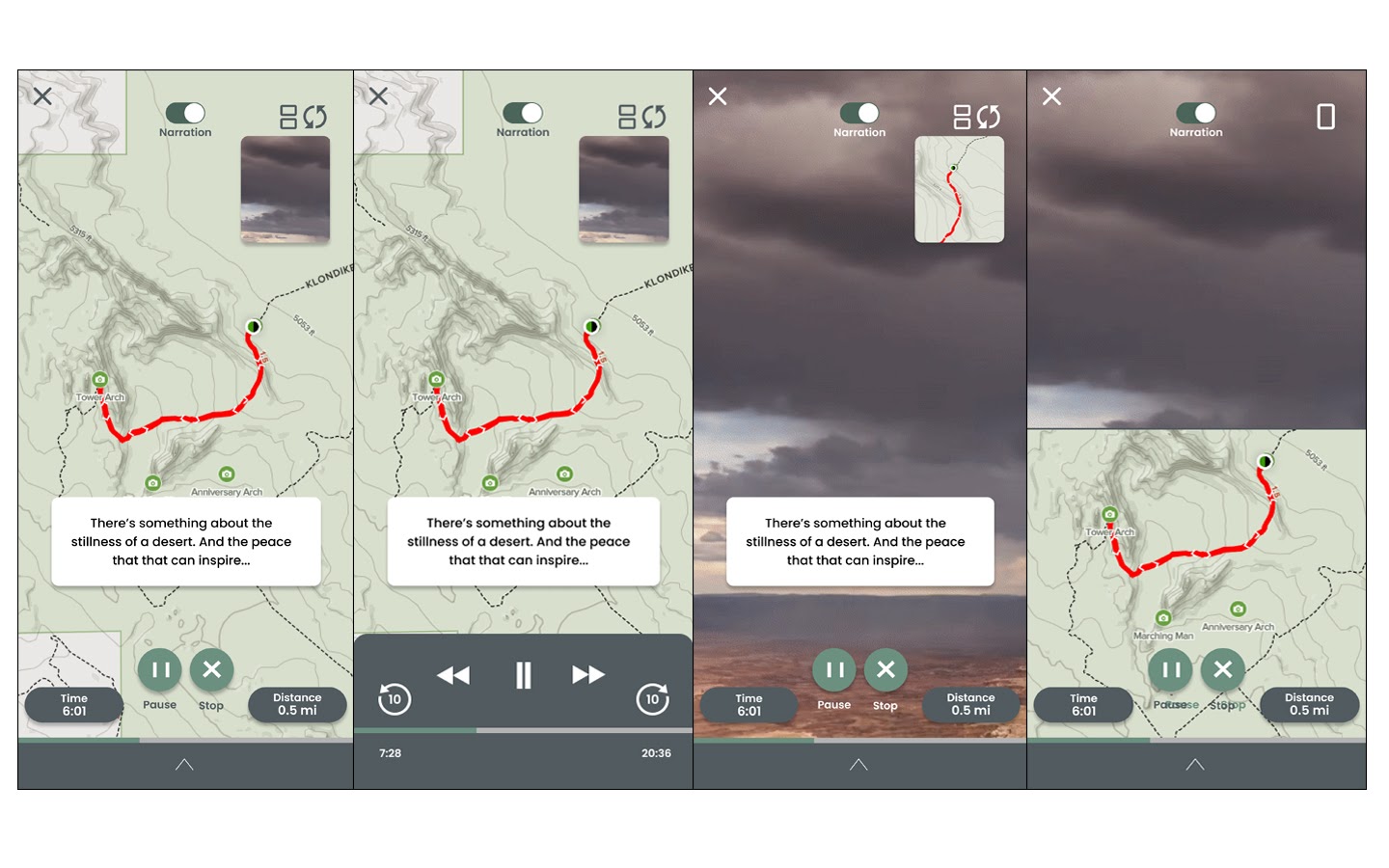

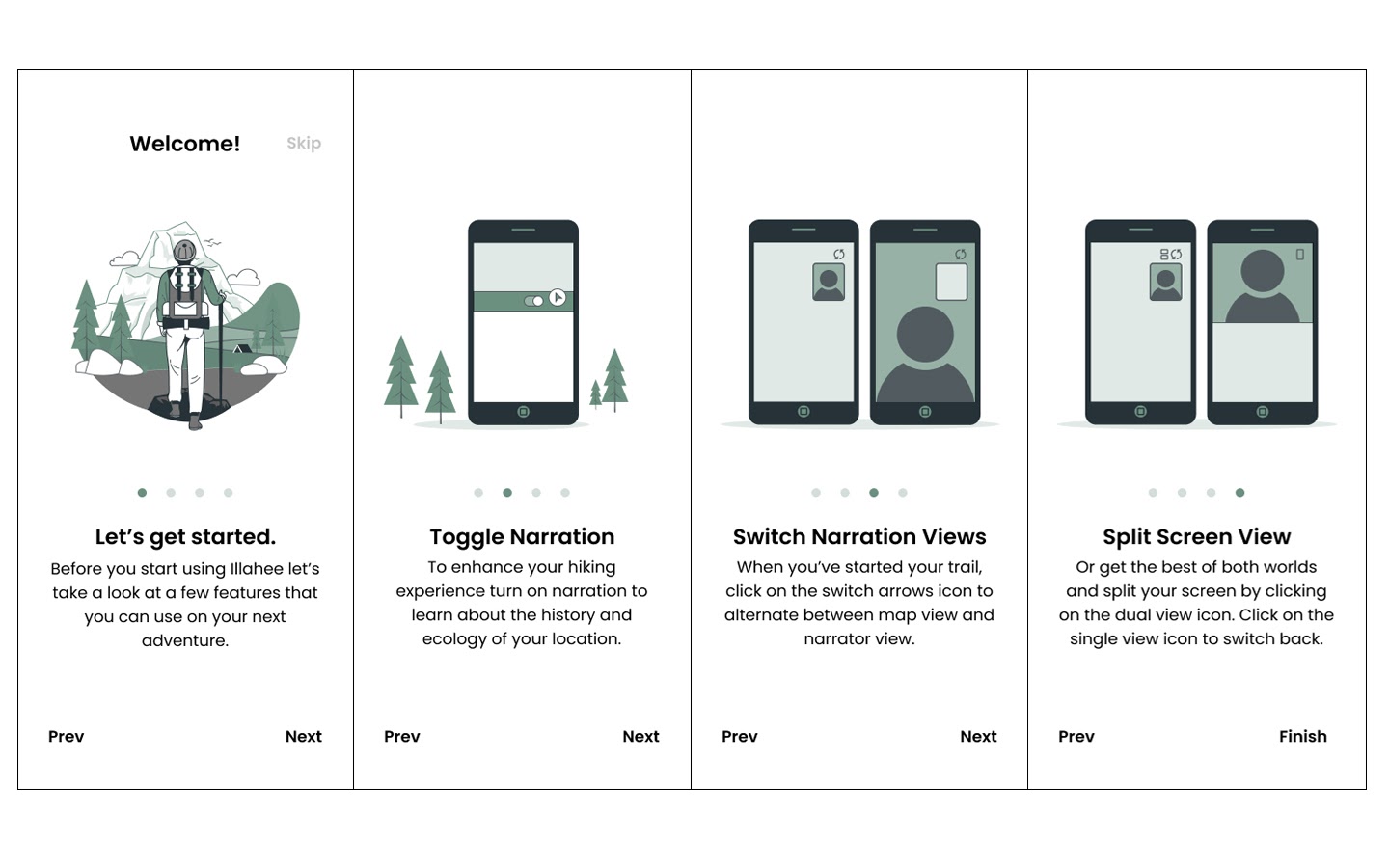

The concept of pluralistic storytelling as a reframing

of history is a core tenet of the initial design

approaches to Illahee.

Re-Making Places also stresses the ‘centrality of

physicality and the need for HCI design to adopt methods

and approaches to engage with embodied practices and

sensorial aspects of places,” (p2967) where “material

engagements in place making, socio-political issues, lived

experiences and practices are brought to the fore and

given form.”(Crivellaro et al., 2015, pg. 2967) The

cohesion of physical experience and storytelling aligns

with proposed Indigienous forms of embodiment discussed in

the next section.

The role of HCI in the futures of sovereign Indigenous placemaking

In Culturally Sensible Digital Place-Making: Design of

the Mediated XicanIndio Resolana, authors Martínez, et al.

discuss theoretical and educational needs of decolonized

design as well as lessons learned from their community

based design research for the Mediated XicanIndio

Resolana, a cultural education interface that engages

participants through embodied interaction and community

storytelling.

While the theoretical foundation of this work is

critical for the development of decolonized HCI, most

relevant to our research is the importance of embodied

interaction and the role this interaction in building

“understanding of indigenious community knowledge systems

for indigenious ways of learning.” (Martinez et al., 2010,

pg. 165)

For the purposes of understanding how digital

placemaking and storytelling could support sovereignty

efforts, it is critical that the method of learning “take

place through embodied and lived experience.” (Martinez et

al., 2010, pg. 165)

Most interestingly, Martinez, et al. posit that beyond

indigenous knowing, there is indegnious being - a

reflection of the local community requiring presence of

the local community, through a practice of interaction

with others within the context of a situated environment.

This practice of indigenious being is central to our

design research: situating first person or testimonio

storytelling within an associated ecological environment

as a practice of reciprocity and accountability.

Martinez, et al. emphasize the critical nature of

participatory design by local Indigenous communities -

learning is often considered a sacred act (p. 168) and the

expository nature of sharing ‘knowledge’ with unwilling or

unengaged audiences could be extractionary and deeply

harmful. The concept of sovereignty must extend to how and

what knowledge is shared - and how that learning is

received.